Urban Design Build Studio Statement

"The Urban Design Build Studio (UDBS) is a collaborative of students, professors, and allied professionals who work with community residents on implementation of appropriate, affordable, replicable design solutions. It is a Public Interest Design Entity that utilizes participatory design processes to strengthen capacities of community residents. Each year a cohort of vertically integrated students ranging in size from 12 to 25 work with communities to identify, design, and implement catalytic projects that address relevant social and economic needs. Since 2008, the UDBS has worked on real projects, bringing university students off campus to be inspired by people who are actively advocating for their communities. Project development is dependent on the engagement of local residents, clients, and teaching students to be thoughtful architects, makers, and citizens stakeholders to help students understand existing neighborhood conditions and future aspirations. The design process is predicated on collective intelligence, is highly collaborative, and involves hands on making as an essential design tool."

- Urban Design Build Studio

Full 2018-2019 Urban Design Build Studio Cohort Listed Below

The Concentrated Poverty Matrix

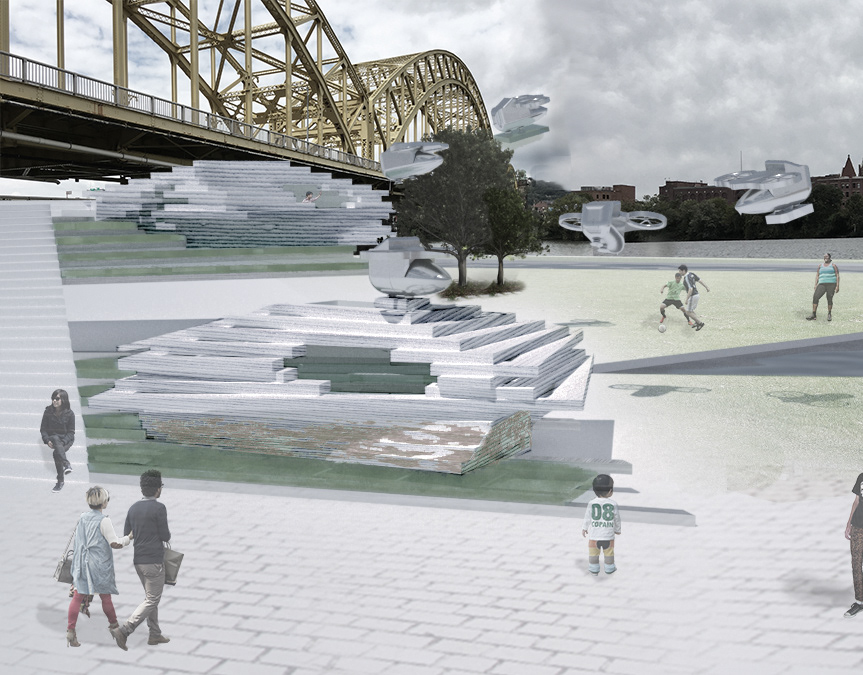

Produced by the 2017-2018 Urban Design Build Studio Cohort

The Concentrated Poverty Matrix produced by the 2017-2018 Urban Design Build Studio Cohort

Context Via Inherited Work

The work that the Urban Design Build Studio does focuses on addressing issues of concentrated poverty, specifically in the context of Pittsburgh. Areas of concentrated poverty are defined by census tracts where 40% or more of its residents live below the federal poverty threshold and generally refers to a density of socio-economic deprivation confined to a specific geographic area. Due to a history of systematic de jure and de facto segregation, areas of concentrated poverty are disproportionately inhabited by minority groups with 25.2% of African Americans and 7.5% of white Americans living in these areas in the United States. In regards to Pittsburgh, these divisions of race and economic class become blindingly obvious with massive disparities of wealth and extremely homogenic demographics. In one specific case of two neighborhoods sharing a common border, Homewood and Point Breeze portray this severe division. Homewood’s median household income is $20,400 and the neighborhood’s population is 92.84% African American. Point Breeze, on the other hand, has a median household income of $109,300 and 80.55% of the neighborhood’s population is white. These divisions become evident in the architectural and urban landscape, and thus, how can architecture be applied as a catalyst and agent to facilitate more diversity in neighborhoods in regards to both demographics and wealth?

Context Via Literature

In order to more quickly begin to grasp the complex issues and aspects of designing housing in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh, PA, the Urban Design Build Studio was tasked with reading through and comprehending the vast web of issues described in Witold Rybczynski’s Home: A Short History of an Idea, Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law, and Matthew Desmond’s Evicted. These collections of stories and analysis begin to portray the extent of complexity embedded in the idea of a home, the role of policy in furthering segregation in the United States, and the social, economic, and political issues tied to concentrated poverty. Witold Rybczynski’s Home: A Short History of an Idea explores the idea of comfort and how the concept has evolved over time. It details how then comfort facilitates the development of the house's role and social customs. Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law explains the history of de facto segregation through targeted policy decisions that manufactured the wicked problem of concentrated poverty that is faced today. Lastly, Matthew Desmond’s Evicted uses takes a deep dive into the lives of low-income families struggling with finding housing, homelessness, and eviction, as well as all of the backstory that contextualizes what makes it such a challenge that is both in and outside of their control. While a small slice of understanding of much greater problems and systems, these three books provided a deeper knowledge that what I previously had of the context in which we work within.

Lexicon

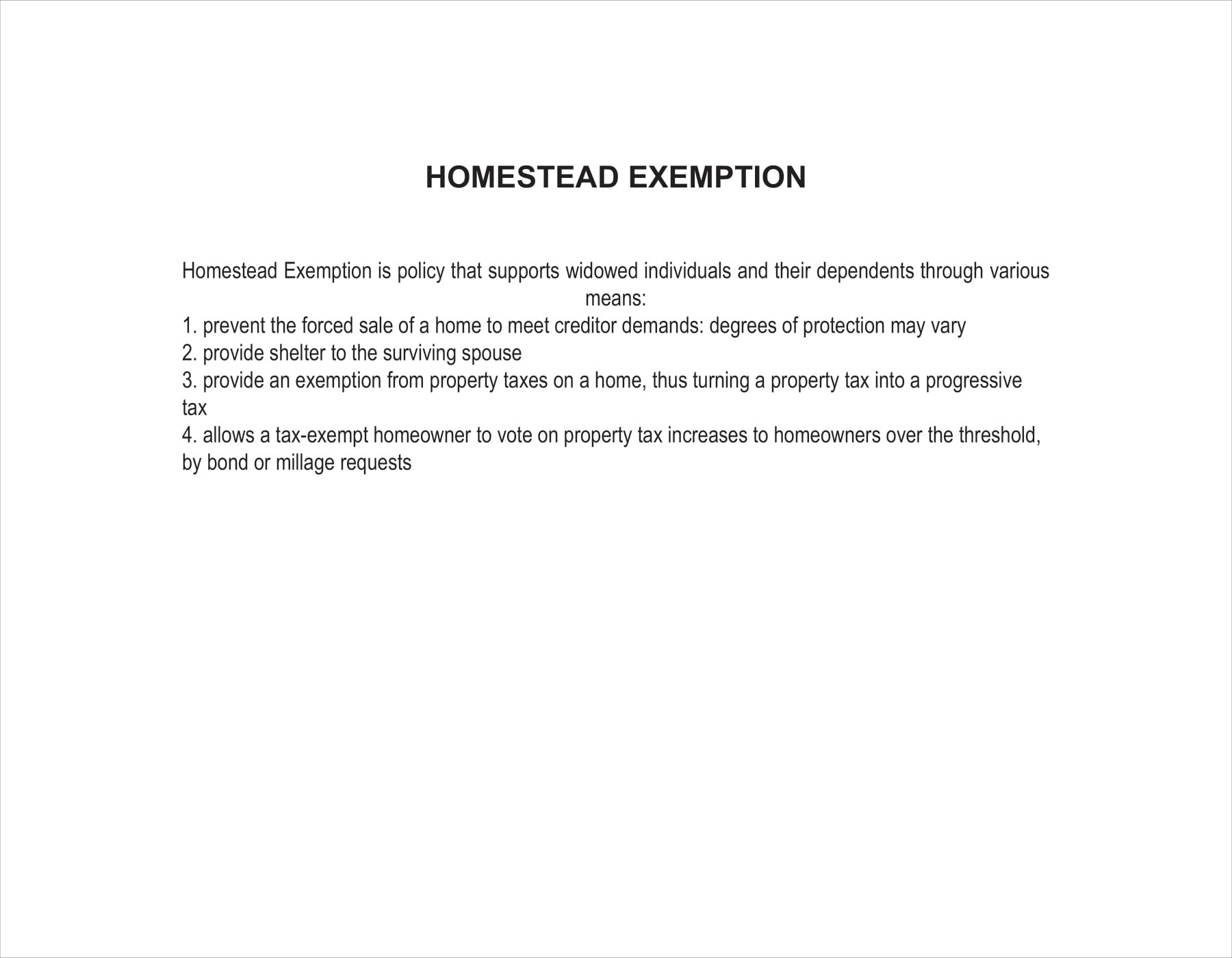

To better familiarize the UDBS with the complex network of terminology required to discuss effectively and intelligently about issues of concentrated poverty, we were assigned a list of words and phrases that have been mentioned during the DECONSTRUCTING BLIGHT introductory presentation at ELDI on August 28, 2018, on the September 07/14 site visits, in studio, and through some of the literature that we have read (Color of Law by Richard Rothstein and Evicted by Matthew Desmond). From the list of recurring vocabulary, we were tasked with generating complementary imagery, definitions, and examples to explain the terms. I chose to explain the concepts eminent domain and Homestead Exemption.

Exploring Pittsburgh

Although I was unaware and less familiar with the City of Pittsburgh before, exploring the city more and looking more closely while a part of the studio allowed me to realize new aspects of the city that I had not seen before.

Congregation B'Nai Israel

While exploring East Liberty, I came across the Congregation B’Nai Israel designed by Henry Hornbostel, a historic synagogue in East Liberty that has since fallen out of use. After some research, I came to realize that critical to the landmark’s closing in June of 1995 was a flurry of issues including Pittsburgh’s Urban Renewal agenda in the 1950s and the accompanying national policy at the time. “Spurred by the U.S. Housing Act of 1949" (Hagerty), urban renewal was a process practiced across the United States in the early 1900s which involved municipal governments exercising eminent domain to buy up private property to then sell to developers to build on. While in some cases urban renewal found success in improving the quality of life in cities, in Pittsburgh’s East Liberty and Hill District, urban renewal was a catastrophic failure. There, the “$58 million urban-renewal plan demolished 1,100 homes and relocated 3,900 people” (Hagerty). This failed effort, coupled with new vehicular technology and investment in highways, caused “people [to leave] Pittsburgh for new suburbs such as West Mifflin, Mount Pleasant, Shaler, Penn Hills, and Oakmont” (Fitzpatrick). This massive population shift was made possible by the G.I. Bill, “which gave World War II veterans access to long-term mortgages backed by the Veterans Administration” (Fitzpatrick). However, these opportunities left out people of color as “banks generally wouldn’t make loans for mortgages in black neighborhoods, and African Americans were excluded from the suburbs by a combination of deed covenants and informal racism” (Callahan). These policies, agendas, and events occurred in parallel resulting in the concentration of poverty in East Liberty and the Hill District. Thus, the abandonment of the Congregation B’Nai Israel isn’t the random movement of a large population of Jewish people to the suburbs. The history of this synagogue rather hints towards the insidious racially-motivated forces that undermined the African American community’s capacity to develop wealth and contributed to conditions of concentrated poverty present in many urban areas today.

Sources

Callahan, David. “How the GI Bill Left Out African Americans.” Demos, Demos, 11 Nov. 2013, www.demos.org/blog/11/11/13/howgi-bill-left-out-african-americans.

Fitzpatrick, Dan. “The Story of Urban Renewal.” Ellsworth Woman Is the Last Living Child of a Little Bighorn Survivor, 21 May 2000, old. post-gazette.com/businessnews/20000521eastliberty1.asp.

Hagerty, James R. “A Neighborhood’s Comeback.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 18 July 2012, www.wsj.com/ articles/SB10001424052702303612804577533112214213358.

Change

In the process of extending the boundaries of the Neighborhood Map, I happened to stumble upon an anomaly. As I was gathering my bearings by alternating between the plan and perspective views to begin understanding the dimensional quality of the area, I noticed a particular building that looked completely different as I crossed the two views. After a bit of research on Pittsburgh’s Real Estate Portal, I found out that the property that had stood out was owned by East Liberty Development Inc. (ELDI). The transformation of the site portrays the significance of addressing issues of blight. While it may be difficult to quantify the statistical impact of a blighted property on its surrounding context, “recent research illustrates the short term benefits [of calculated demolitions of blighted and vacant properties] accrued to adjacent or nearby properties, such as increase in property values and decreases in crime” (de Leon et Schilling). And although deconstruction methods should be considered over the demolition due to its negative environmental and health impacts, a study by Dynamo Metrics in 2015 “found that demolition investment from the Hardest Hit Fund in selected areas of Detroit helped to stabilize those markets [with each] demolition within Detroit’s Hardest Hit Fund zones [increasing] the value of occupied single family homes within 500 feet by 4.2 percent” (de Leon et Schilling). Whereas a blighted or vacant property may cause the devaluation of nearby properties, a functioning and occupied property can contribute to stability and potentially boost property values near it. At the beginning of the studio, the UDBS visited ELDI and were able to learn about the history of Pittsburgh and ELDI’s involvement in that process. Although it has made mistakes in the past, ELDI has also taken great strides in the realm of pushing East Liberty to be a more diverse neighborhood. ELDI has worked to ensure that of 981 total rental units in East Liberty, that 40% of them are low income affordable housing for the next 30 years or more via Section 8, where renters pay 30% of their monthly income with the rest subsidized. Furthermore, ELDI is making use of many other funding sources and strategies for the purpose of shaping East Liberty into a mixed income community marked not by stark contrast of the rich and poor, but rather consistent quality housing worthy of calling home.

Sources

Leon, Erwin de, and Joseph Schilling. “Full Report.” Urban Institute, Urban Institute, 11 Apr. 2017, www.urban.org/research/publication/ urban-blight-and-public-health/view/full_report.

Project Picket Fence

Over the course of the semester’s many site visits and excursions into Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods, I have come across several sites labeled “Project Picket Fence Mayor, Tom Murphy 1994”. These lots featured simple landscaping and a small wooden picket fence only a couple feet tall with a sign nailed to it. And although there is little documentation of the project itself online, there was a mix of both formal and informal media from news articles to blogs that painted the public opinion of the project. One source documented that the project began “in 1994, [when] Mayor Tom Murphy had the idea to clean up some of the city’s vacant lots, [placing a] picket fence around them, and [showcasing] them as properties for sale” (Ninety Hoods). This initiative however was soon cut short in the summer of 1995 when the “City Council balked when it learned that in some cases, the weeds had grown back taller than the fences” (McArdle). Many of these sites to this day remain vacant though, and thus, the project’s impact has been for the most part a visual improvement with no real positive impact on the communities in which these vacant lots reside. Even so, the project, over the course of a year, “had cleaned up 80 lots, with 19 groups pledging to maintain them” (Ninety Hoods), portraying some level of interaction with communities and success, albeit on a surface level. Although positive in intent and simple in concept, this project reveals deeper issues tied to disinvestment and segregation in Pittsburgh which require much more precision, care, and complexity to address productively. This project has left me wondering, however: How should we engage these discussions of topics of such complexity? How can lasting programs with continuous, meaningful impact be created?

Sources

McArdle. “Mayor Tom Murphy.” Pittsburgh Metblogs » Mayor Tom Murphy, Bode Media, 28 Feb. 2007, 4:52 PM, pittsburgh.metblogs. com/2007/02/28/mayor-tom-murphy/.

Ninety Hoods. “Project Picket Fence.” Ninety Hoods, Wordpress, 25 May 2010, ninetyhoods.wordpress.com/2010/05/25/project-picketfence/.

Kingsley Association Community Meeting

I had the opportunity to attend a community meeting at the Kingsley Association to discuss three key points in regards to the promotion of Fair Housing policy in Pittsburgh: Development/Zoning, Landlord/Tenant Relationships, and Education/Outreach/Training. During the meeting, moderators led discussions on the drafted policies and then opened the floor for amendment proposals. Comments were recorded by a typist and attendees were informed that an online process would also allow people to make further comments or feedback. In attending this event, it was humbling to see the insight and perspective that people from all different backgrounds could provide to enhance the proposed policy, as well as the passion and drive in the discussions to find ways to make the system more just. The proposals discussed during the meeting ranged from policy revising Pittsburgh’s zoning code regulations to others proposing to improve outreach and education on a number of topics including the rights and available resources of protected classes. The community meeting generated much needed discussion in a safe environment which respected everyone’s opinions and highlighted the points raised. In all, it was a great opportunity to interact with engaged citizens who joined the conversation of how to positively influence their community.

2018-2019 Urban Design Build Studio Cohort:

Bachelor of Architecture (B.Arch)

Alison Katz+ [4th Year], Alex Lin+ [4th Year], Christine Zhu+ [4th Year], Miranda Ford^ [5th Year], Gargi Lagvankar+ [5th Year], Timothy Khalifa+ [5th Year]

Master of Architecture (M.Arch)

Anthony Kosec [2nd Year], Ever Clinton [1st Year], Fernanda Mazzilli [1st Year], Jacob Clare [2nd Year], Jay Tyan [2nd Year], Kyle Bancroft+ [1st Year], Lana Kozlovskaya [1st Year], Ryan Smerker+ [1st Year], Shailaja Patel [1st Year], Srinjoy Hazra [1st Year], Yash Khemka^ [2nd Year], and Yashwitha Maram Reddy [1st Year]

Master of Science in Sustainable Design

Architecture-Engineering-Construction Management (AECM)

Key

^ = One Semester + = Summer Internship

Check out some of the UDBS Projects I've had the chance to be a part of!

For more information and context about past UDBS projects, feel free to check out the UDBS Brochure and the UDBS Tumblr !